The March goes on

By March, the worst of the winter would be over. The snow would thaw, the rivers begin to run and the world would wake into itself again.

Not that year.

Winter hung in there, like an invalid refusing to die. Day after grey day the ice stayed hard; the world remained unfriendly and cold.

From the children’s book Odd and the Frost Giant by Neil Geiman

A few thoughts…

March is that special time of the year where nature pulls off its own magic trick. The once barren, white desert of wintertime is replaced with a sea of pastel colours. Flowers bloom on the branches of trees that were seemingly teetering on the edge of life just weeks ago. As the thick layer of snow melts away, revealing the lush green meadows below, many animals awaken from their slumber, taking in the soft glow of the rising sun for the first time in months while birds make the long journey home, returning from their tropical vacation in faraway lands. Up in the heavens, strokes of white scatter the deep blue canvas, and between its cracks, the bright sun seeps through, blanketing the world with its light and warmth, reminding all across the vast lands that the dark wintry days are finally over. One who is surrounded by such greatness and wonder, upon taking a deep breath, will smell the very essence of life.

The Pink Orchard by Vincent Van Gogh (1888)

Yet, the reality of life reflects a completely different image of nature’s scenery. With the worsening of the Covid-19 situation causing the cancellation of not only RoboCup, but many other robotics competitions as well, our disappointment is shared worldwide. For most of us, this would have been our last year participating in RoboCup. It is even more poignant to note how in the past few years, when we were given countless opportunities, we were always unprepared and left in a state of frenzy. Yet now, when we were finally “more prepared than ever to forge new frontiers in the new year”, to make our final stand and end this decade long journey of robotics on a high, it was the world that fell into hysteria instead. Alas, when faced with the irony of the absurd world, what can we do, as passengers on this roller coaster of chaos, but to force a helpless smile and move on…

Progress now is way behind our original schedule since many of our shipments were delayed. We are also working much slower now since our actual deadline for completion has been “shifted” to next year, allowing us to balance our time with other things such as academics and new non-RoboCup related projects (hint hint). Nonetheless, we still made some progress in March and here are our key achievements.

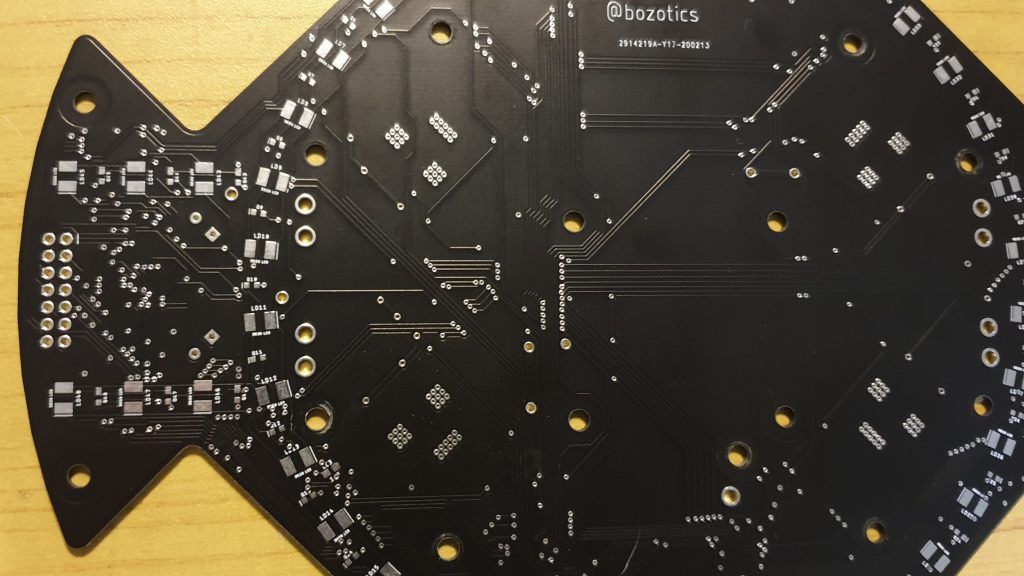

PCB (Open)

Many of our remaining electronic parts arrived over the course of the month. All the circuits in our PCB surprisingly worked. However, we did encounter a few design flaws in them, mainly the 1st layer.

The 60V circuitry for the solenoid and 12V connectors for the motors are very close to the 3.3V power for the LED light ring. We will need to insulate the bottom of the PCB to ensure accidental shorting does not occur.

The motor and battery connectors (left) near to the LEDs (right)

Also, due to some miscalculations, the back of a motor was too close to the 3.3V pin for the mouse sensor, which blocked us from being able to insert the connector for the sensor. In the end, we wired the mouse sensor up from a spare 3.3V pin.

All these problems will certainly be fixed in the follow-up version of the PCB for our robot next year.

PCB (Lightweight)

For the Lightweight PCBs, most of the important parts such as the motors and IR sensors are working perfectly. However, we are currently facing a problem with the I2C communication for the TOF sensors on the fourth layer, although not much troubleshooting has been done for it yet, so we are not quite sure what is causing it as of now.

There is also one very, very dumb mistake for these PCBs. Due to certain wrong configurations in EAGLE, all of the vias are not tented. This is especially bad when it comes to the really complicated boards like the first layer since any stray metal part can easily short it. Sigh…

Pimples everywhere...

In addition, Lightweight progress may be put on hold or terminated. This is because we have always used Lightweight as an introduction league to guide our first timers with the basics before they go into the Open category and thus, there will be a completely new batch of students who will have to build a completely new set of robots next year. But nothing is confirmed yet, so we’ll see how it goes.

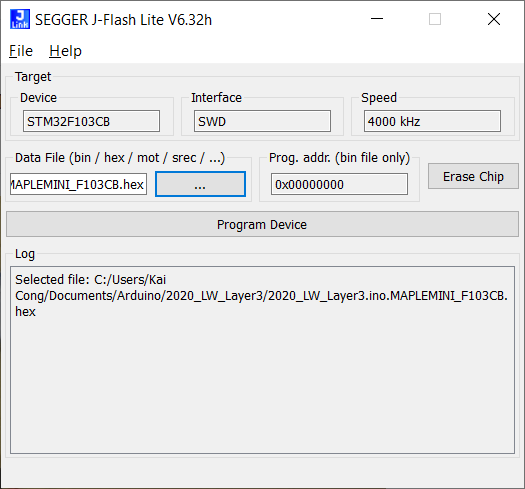

STM32 programming

Our STM32 was modeled from the Maple Mini board. However, one problem with the Maple Mini was that the USB communication with Arduino is quite unreliable, e.g. program could not be uploaded, hanging, etc. Thus, during our “Test PCB” phase, when we uploaded the Maple Mini bootloader and downloaded programs into the STM32 over USB, there was the same unreliability, where it stopped and started working at random times.

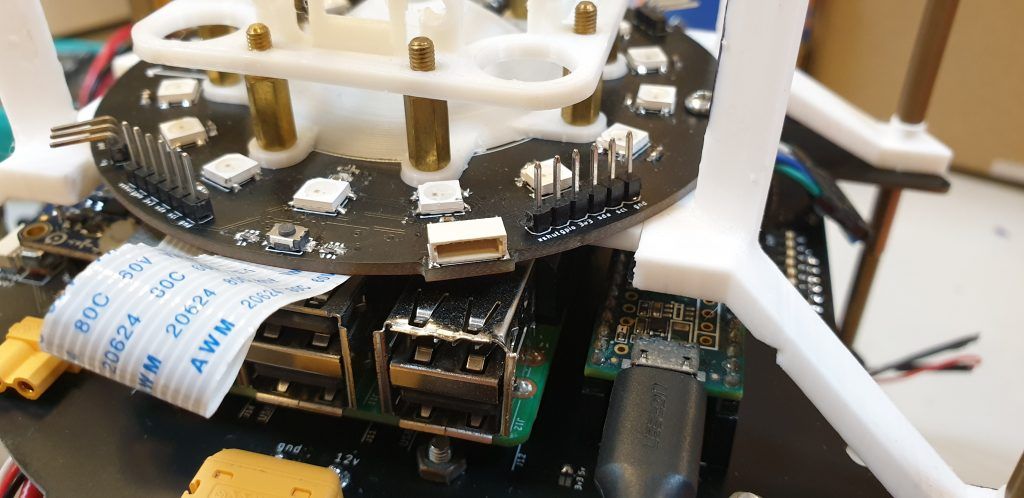

As such, we decided to use the SWD protocol to upload programs directly into the STM32. On our PCB, we breakout the SWD, power and TX/RX pins into a 6 pin JST-SH1.0 connector.

JST-SH1.0 connector on the 4th layer of Open robot

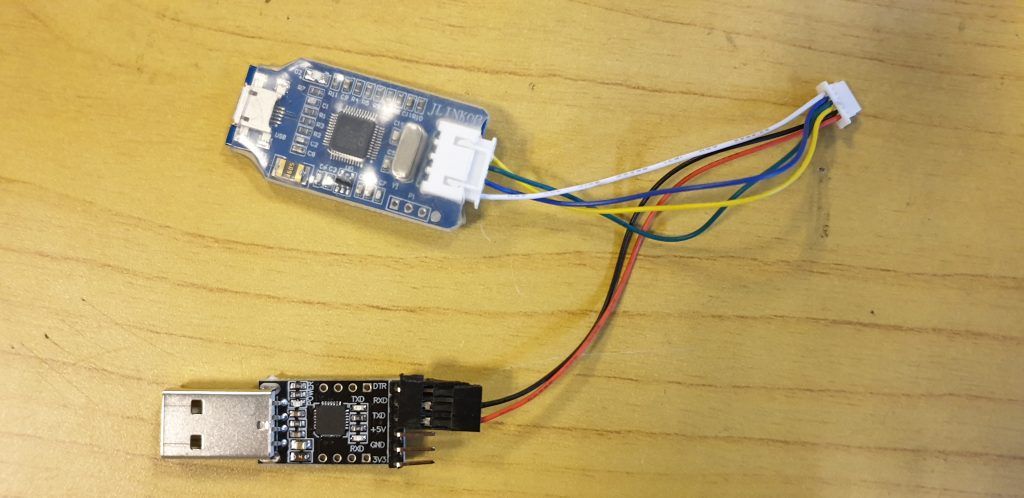

Using a J-Link OB V8 debugger we are able to upload the compiled .hex files of our programs using the Segger J-Flash software. Also, with a USB to UART converter connected to the TX/RX pins, we can still use Arduino’s Serial Monitor to view data the same way as a USB connection would.

J-Link and USB to UART converter wired to the JST-SH1.0 connector

Screenshot of J-Flash software

Intra-robot communication

Since our sensors on the different layers are communicating with 4 different STM32 micro-controllers, we need a way to communicate with them from the main controller, the Teensy.

We chose UART instead of other communication protocols like I2C and SPI. This is because I2C is too sensitive, especially the cross-layer wires that will be highly susceptible to EMI from the motor, while SPI slave mode is quite difficult to implement on our STM32 micro-controllers and would require more wires. However, UART, albeit rather slow, is the simplest to implement of all the protocols, requires only 2 wires and is relatively robust against noise. Besides, our Teensy has 6 serial ports so we do not need to fear about running out of them.

We use a standardised format for each string of data. It starts out with a character that indicates what type of data it is (e.g. Light sensor = L), followed by the data itself and finally the vertical bar | as a delimiter. This data would be read into a buffer and upon reading the vertical bar, a function would be called to process it. An example buffer would be B100,90| which means the ball (B) is 100 cm away at a 90 degree angle relative to the robot.

For the light sensors, the thresholds are processed on the STM32 and data is represented in 5 bytes (for Open, with 40 sensors) or 6 bytes (for Lightweight, with 48 sensors). Each bit in the bytes represents the state of the light sensors (1 = detected line, 0 = not detected). For example, if the 1st byte is 20 (B00010100), that would mean the 3rd and 5th sensor is detecting the line.

The communication between the Raspberry Pi and Teensy is very critical since there is a huge amount of data being sent between them (ball position, ball’s predicted position, yellow and blue goal positions and field area coordinates). Thus, the speed of communication is very important and we tested out what the maximum baud rate could be used between the two controllers. Using a serial loopback test on the Raspberry Pi, we found the communication to be stable up to 2 million bits/sec, which is just nice since the fastest speed the Teensy can communicate with a 0% error rate is also 2 million bits/sec.

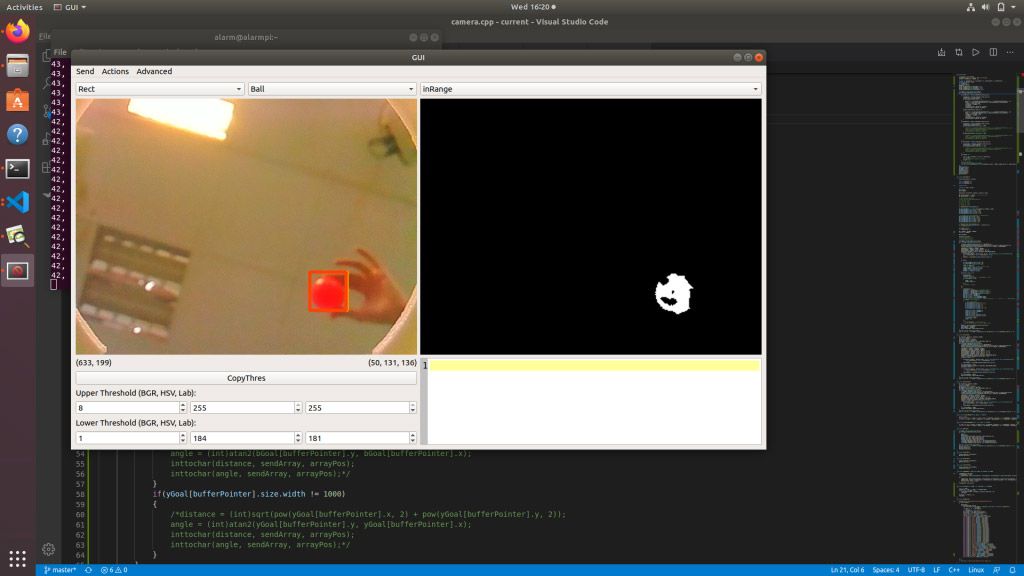

GUI

Some improvements were added to the GUI over the month. An additional camera window was created, which can be toggled to a different mode from the main camera window. Hence, when calibrating the threshold in the main window, the results can be viewed immediately in the secondary window instead of having to switch modes like in the older version. Under the secondary window includes a mini notepad as well for recording threshold values or other information. Also, all configuration parameters other than the threshold values have been hidden to make the GUI less cluttered. They can be toggled to be shown under the ‘Advanced’ tab at the top left corner.

Screenshot of new GUI window

Camera

A new version of the object tracking program (for ball, goal and field) was created to deal with a rising number of issues we faced with the original version.

In the original program, the CPU utilisation was around 80% and the frame capture rate was at 65 FPS, far below what we had planned to achieve. In hopes of optimising the code, we tried testing specific parts of the code, only to add to our confusion as even more weird problems popped up. For example, when a usleep was added to the main thread so that it does not run on an empty while loop, the frame capturing rate decreased. This is the exact opposite of what we expected to see, since less CPU was being used, the FPS should have increased! While we are still not fully sure why this happens, our best guess would be that usleep interferes with the other threads.

Anyways, with many problems identified in the original program, we embarked on creating a second version to specifically address them. The new version has a CPU utilisation of half the original, at only 40%. The frame capture rate is also back at 90 FPS again, exactly what we wanted. Some of the key improvements in this second version include:

-

Instead of running a thread on an empty loop — constantly refreshing until a new frame is obtained — a condition variable is used to send a signal to the respective processing threads, releasing it from a block.

-

The use of mutex for thread synchronisation and the prevention of data race has been replaced by atomic variables and circular buffers. Previously, mutex locking and unlocking of the capture frame took up around 2.5 ms. While that might sound like a small amount of time, when considering that the latency in the capturing of frames is around 16 ms, cutting down on this 2.5 ms help reduced the latency significantly.

-

The threads now run on a priority system, allowing for better allocation of CPU resources (priority 1 runs at 90 FPS, priority 2 at 20 FPS and priority 3 at 10 FPS). The priority given to each thread is dynamic, which means that our Teensy can switch the priorities, or even assign 2 threads to the highest priority, as needed during the match (e.g. when chasing for the ball, priority 1 can be assigned for ball detection, but once we have possession of the ball in our dribbler, priority 1 can be assigned for goal detection instead). In the video below, the ball is assigned with priority 1 while the goals are in priority 2. Hence the goals detection are seen flickering as they are only being detected about once every 5 frames.

With these implementations, our processing of top priority objects can be done at 90 FPS with a latency of around 13 ms.

Conclusion

On the one hand, this is definitely a disheartening end to the 2020 RoboCup journey for all of us, but on the other hand, perhaps this is a reminder for us to look beyond just the competition itself. We have always been overly focused on HOW we do what we do that we often forget about WHY. It is times like this, when we still continue doing what we do, with no conceivable end in sight, that really forces us to ponder about the purpose of it all…

Nonetheless, we know that we are very fortunate to still be able to continue, “business (somewhat) as usual”, and as long as this remains possible, we will definitely not stop. In the meantime, stay safe, stay healthy, stay strong! 💪